Also see:

Gelatin, stress, longevity

Thyroid peroxidase activity is inhibited by amino acids

Gelatin, Glycine, and Metabolism

Gelatin > Whey

Health Benefits of Glycine

Gelatin, stress, longevity

The anticatabolic effect of glycine

Enzyme to Know: Tryptophan Hydroxylase

Whey, Tryptophan, & Serotonin

Omega -3 “Deficiency” Decreases Serotonin Producing Enzyme

Hypothyroidism and Serotonin

Estrogen Increases Serotonin

Role of Serotonin in Preeclampsia

Maternal Ingestion of Tryptophan and Cancer in Female Offspring

Tryptophan Metabolism: Effects of Progesterone, Estrogen, and PUFA

Anti-Serotonin, Pro-Libido

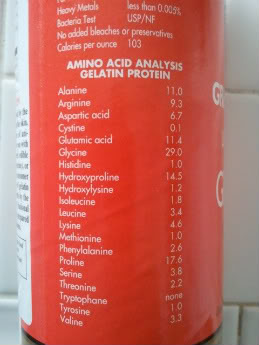

“The selection of proteins should minimize the amino acids tryptophan (which is the precursor of serotonin) and cysteine (which, like tryptophan, suppresses thyroid function, by including gelatin and fruits. Gelatin is 22% glycine, which protects the lungs and other organs against toxins and inflammatory agents, and many fruits are “deficient” in tryptophan and cysteine.” -Ray Peat, PhD

Am J Physiol. 1999 Nov;277(5 Pt 1):L952-9.

Production of superoxide and TNF-alpha from alveolar macrophages is blunted by glycine.

Wheeler MD, Thurman RG.

Glycine blunts lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced increases in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca(2+)](i)) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) production by Kupffer cells through a glycine-gated chloride channel. Alveolar macrophages, which have a similar origin as Kupffer cells, play a significant role in the pathogenesis of several lung diseases including asthma, endotoxemia, and acute inflammation due to inhaled bacterial particles and dusts. Therefore, studies were designed here to test the hypothesis that alveolar macrophages could be inactivated by glycine via a glycine-gated chloride channel. The ability of glycine to prevent endotoxin [lipopolysaccharide (LPS)]-induced increases in [Ca(2+)](i) and subsequent production of superoxide and TNF-alpha in alveolar macrophages was examined. LPS caused a transient increase in intracellular calcium to nearly 200 nM, with EC(50) values slightly greater than 25 ng/ml. Glycine, in a dose-dependent manner, blunted the increase in [Ca(2+)](i), with an IC(50) less than 100 microM. Like the glycine-gated chloride channel in the central nervous system, the effects of glycine on [Ca(2+)](i) were both strychnine sensitive and chloride dependent. Glycine also caused a dose-dependent influx of radiolabeled chloride with EC(50) values near 10 microM, a phenomenon which was also inhibited by strychnine (1 microM). LPS-induced superoxide production was also blunted in a dose-dependent manner by glycine and was reduced approximately 50% with 10 microM glycine. Moreover, TNF-alpha production was also inhibited by glycine and also required nearly 10 microM glycine for half-inhibition. These data provide strong pharmacological evidence that alveolar macrophages contain glycine-gated chloride channels and that their activation is protective against the LPS-induced increase in [Ca(2+)](i) and subsequent production of toxic radicals and cytokines.

Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004 Dec;287(6):R1387-93. Epub 2004 Aug 26.

Glycine intake decreases plasma free fatty acids, adipose cell size, and blood pressure in sucrose-fed rats.

El Hafidi M, Pérez I, Zamora J, Soto V, Carvajal-Sandoval G, Baños G.

The study investigated the mechanism by which glycine protects against increased circulating nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), fat cell size, intra-abdominal fat accumulation, and blood pressure (BP) induced in male Wistar rats by sucrose ingestion. The addition of 1% glycine to the drinking water containing 30% sucrose, for 4 wk, markedly reduced high BP in sucrose-fed rats (SFR) (122.3 +/- 5.6 vs. 147.6 +/- 5.4 mmHg in SFR without glycine, P < 0.001). Decreases in plasma triglyceride (TG) levels (0.9 +/- 0.3 vs. 1.4 +/- 0.3 mM, P < 0.001), intra-abdominal fat (6.8 +/- 2.16 vs. 14.8 +/- 4.0 g, P < 0.01), and adipose cell size were observed in SFR treated with glycine compared with SFR without treatment. Total NEFA concentration in the plasma of SFR was significantly decreased by glycine intake (0.64 +/- 0.08 vs. 1.11 +/- 0.09 mM in SFR without glycine, P < 0.001). In control animals, glycine decreased glucose, TGs, and total NEFA but without reaching significance. In SFR treated with glycine, mitochondrial respiration, as an indicator of the rate of fat oxidation, showed an increase in the state IV oxidation rate of the beta-oxidation substrates octanoic acid and palmitoyl carnitine. This suggests an enhancement of hepatic fatty acid metabolism, i.e., in their transport, activation, or beta-oxidation. These findings imply that the protection by glycine against elevated BP might be attributed to its effect in increasing fatty acid oxidation, reducing intra-abdominal fat accumulation and circulating NEFA, which have been proposed as links between obesity and hypertension.

Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000 Aug;279(2):L390-8.

Dietary glycine blunts lung inflammatory cell influx following acute endotoxin.

Wheeler MD, Rose ML, Yamashima S, Enomoto N, Seabra V, Madren J, Thurman RG.

Mortality associated with endotoxin shock is likely mediated by Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, and circulating neutrophils. Acute dietary glycine prevents mortality and blunts increases in serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) following endotoxin in rats. Furthermore, acute glycine blunts activation of Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, and neutrophils by activating a glycine-gated chloride channel. However, in neuronal tissue, glycine rapidly downregulates chloride channel function. Therefore, the long-term effects of a glycine-containing diet on survival following endotoxin shock were investigated. Dietary glycine for 4 wk improved survival after endotoxin but did not improve liver pathology, decrease serum alanine transaminase, or effect TNF-alpha levels compared with animals fed control diet. Interestingly, dietary glycine largely prevented inflammation and injury in the lung following endotoxin. Surprisingly, Kupffer cells from animals fed glycine for 4 wk were no longer inactivated by glycine in vitro; however, isolated alveolar macrophages and neutrophils from the same animals were sensitive to glycine. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that glycine downregulates chloride channels on Kupffer cells but not on alveolar macrophages or neutrophils. Importantly, glycine diet for 4 wk protected against lung inflammation due to endotoxin. Chronic glycine improves survival by unknown mechanisms, but reduction of lung inflammation is likely involved.

Glycine protects against fat accumulation in the alcohol-induced liver injury (Senthilkumar, et al., 2003), suggesting that dietary gelatin would complement the protective effects of saturated fats. -Ray Peat, PhD

Both proline and glycine (which are major amino acids in gelatin) are very protective for the liver, increasing albumin, and stopping oxidative damage. -Ray Peat, PhD

Pol J Pharmacol. 2003 Jul-Aug;55(4):603-11.

Glycine modulates hepatic lipid accumulation in alcohol-induced liver injury.

Senthilkumar R, Viswanathan P, Nalini N.

We studied the effect of administering glycine, a non-essential amino acid, on serum and tissue lipids in experimental hepatotoxic Wistar rats. All the rats were fed standard pellet diet. Hepatotoxicity was induced by administering ethanol (7.9 g kg(-1)) for 30 days by intragastric intubation. Control rats were given isocaloric glucose solution. Glycine was subsequently administered at a dose of 0.6 g kg(-1) every day by intragastric intubation for the next 30 days. Average body weight gain at the end of the total experimental period of 60 days was significantly lower in rats supplemented with alcohol, but improved on glycine treatment. Feeding alcohol significantly elevated the levels of cholesterol, phospholipids, free fatty acids and triglycerides in the serum, liver and brain as compared with those of the control rats. Subsequent glycine supplementation to alcohol-fed rats significantly lowered the serum and tissue lipid levels to near those of the control rats. Microscopic examination of alcohol-treated rat liver showed inflammatory cell infiltrates and fatty changes, which were alleviated on treatment with glycine. Alcohol-treated rat brain demonstrated edema, which was significantly lowered on treatment with glycine. In conclusion, this study shows that oral administration of glycine to alcohol-supplemented rats markedly reduced the accumulation of cholesterol, phospholipids, free fatty acids and triglycerides in the circulation, liver and brain, which was associated with a reversal of steatosis in the liver and edema in the brain.

Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012 Jun;16(6):728-36.

Glycine alleviates liver injury induced by deficiency in methionine and or choline in rats.

Barakat HA, Hamza AH.

OBJECTIVES:

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is an advanced stage of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) from steatosis. Methionine and choline are important amino acids play a key role in many cellular functions. Glycine is a non-essential amino acid having multiple roles in many reactions. This study aimed to investigate liver damage induced by feeding male albino rats either methionine deficient (MD), choline deficient (CD), or MCD diets. And to clarify the alleviatory effect of dietary glycine supplementation (5%) on reduced complications caused by feeding each of the deficient diets.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

Nutritional status, liver functions, lipids profile, hepatic oxidative stress, hepatic antioxidant enzymes, tumor markers and hepatic fatty acid transport protein gene were assessed.

RESULTS:

Rats fed with either MD or MCD diet had less body weight gain unlike rats fed the CD diet. Liver injury was detected in deficient groups by elevating plasma ALT, AST, ALP, total and direct bilirubin, albumin and protein levels. Lipid accumulation was more prominent in rats fed the MCD or CD diet than in those fed the MD diet. Fatty acid transport protein (FATP) was significantly elevated in the different glycine supplemented groups.

CONCLUSION:

Oral administration of glycine confers a significant protective effect by optimizing all the assessed parameters and gene expression.

Hepatology. 2000 Sep;32(3):542-6.

Glycine prevents apoptosis of rat sinusoidal endothelial cells caused by deprivation of vascular endothelial growth factor.

Zhang Y, Ikejima K, Honda H, Kitamura T, Takei Y, Sato N.

Apoptosis of sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) is one of the initial events in the development of ischemia-reperfusion injury of the liver. Glycine has been shown to diminish ischemia-reperfusion injury in the liver and improve graft survival in the rat liver transplantation model. Here, we investigated the effect of glycine on apoptosis of primary cultured rat SECs induced by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) deprivation. Isolated rat SECs were cultured in EBM-2 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and growth factors including 20 ng/mL VEGF for 3 days. SECs at 3 days of culture showed spindle-like shapes; however, cells started shrinking and detaching from dishes by VEGF deprivation. Apoptosis was detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated d-uridine triphosphate (dUTP)-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining in these conditions. Control SECs contained only a few percent of TUNEL-positive cells; however, they started increasing 4 hours after VEGF deprivation, and the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells reached about 50% at 8 hours and almost 100% at 16 hours after VEGF deprivation. Interestingly, this increase in TUNEL-positive cells after VEGF deprivation was prevented significantly when glycine (1-10 mmol/L) was added to the medium, the levels being around 60% of VEGF deprivation without glycine. Furthermore, strychnine (1 micromol/L), a glycine receptor antagonist, inhibited this effect of glycine, suggesting the possible involvement of the glycine receptor/chloride channel in the mechanism. Moreover, Bcl-2 protein levels in SECs were decreased 8 hours after VEGF deprivation, which was prevented almost completely by glycine. It is concluded that glycine prevents apoptosis of primary cultured SECs under VEGF deprivation.

Glycine, like carbon dioxide, protects proteins against oxidative damage (Lezcano, et al., 2006), so including gelatin (very rich in glycine) in the diet is probably protective. -Ray Peat, PhD

Rev Alerg Mex. 2006 Nov-Dec;53(6):212-6.

Effect of glycine on the immune response of the experimentally diabetic rats.

Lezcano Meza D, Terán Ortiz L, Carvajal Sandoval G, Gutiérrez de la Cadena M, Terán Escandón D, Estrada Parra S.

BACKGROUND:

Hyperglycemia induces protein glycation, disturbing its function, additionally, the glycated products (AGEs) induce by themselves proinflammatory cytokine release that are responsible for insulin resistance. Glycine has been successfully used in diabetic patients to competitively reduce hemoglobin glycation.

OBJECTIVES:

To assess hyperglycemia impact on the immune response and to evaluate if it is possible to reverse it by means of glycine administration.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, with and without glycine administration were challenged with sheep red blood cells, and specific antibody producing cells were accounted. Normal rats were challenged as controls.

RESULTS:

Induced diabetes modifies significantly the humoral immune response capacity versus sheep red blood cells. Also, glycine administration prevents against this deleterious effect.

CONCLUSIONS:

Glycine could be an important therapeutic resource among diabetics to avoid the characteristic immunodeficiencies of this disease.

Infect Immun. 2001 Sep;69(9):5883-91.

Dietary glycine prevents peptidoglycan polysaccharide-induced reactive arthritis in the rat: role for glycine-gated chloride channel.

Li X1, Bradford BU, Wheeler MD, Stimpson SA, Pink HM, Brodie TA, Schwab JH, Thurman RG.

Peptidoglycan polysaccharide (PG-PS) is a primary structural component of bacterial cell walls and causes rheumatoid-like arthritis in rats. Recently, glycine has been shown to be a potential immunomodulator; therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if glycine would be protective in a PG-PS model of arthritis in vivo. In rats injected with PG-PS intra-articularly, ankle swelling increased 21% in 24 to 48 h and recovered in about 2 weeks. Three days prior to reactivation with PG-PS given intravenously (i.v.), rats were divided into two groups and fed a glycine-containing or nitrogen-balanced control diet. After i.v. PG-PS treatment joint swelling increased 2.1 +/- 0.3 mm in controls but only 1.0 +/- 0.2 mm in rats fed glycine. Infiltration of inflammatory cells, edema, and synovial hyperplasia in the joint were significantly attenuated by dietary glycine. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) mRNA was detected in ankle homogenates from rats fed the control diet but not in ankles from rats fed glycine. Moreover, intracellular calcium was increased significantly in splenic macrophages treated with PG-PS; however, glycine blunted the increase about 50%. The inhibitory effect of glycine was reversed by low concentrations of strychnine or chloride-free buffer, and it increased radiolabeled chloride influx nearly fourfold, an effect also inhibited by strychnine. In isolated splenic macrophages, glycine blunted translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-kappaB into the nucleus, superoxide generation, and TNF-alpha production caused by PG-PS. Further, mRNA for the beta subunit of the glycine receptor was detected in splenic macrophages. This work supports the hypothesis that glycine prevents reactive arthritis by blunting cytokine release from macrophages by increasing chloride influx via a glycine-gated chloride channel.

Clin Nutr. 2014 Jun;33(3):448-58. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.06.013. Epub 2013 Jun 26.

Glycine administration attenuates skeletal muscle wasting in a mouse model of cancer cachexia.

Ham DJ1, Murphy KT1, Chee A1, Lynch GS1, Koopman R2.

BACKGROUND AND AIMS:

The non-essential amino acid, glycine, is often considered biologically neutral, but some studies indicate that it could be an effective anti-inflammatory agent. Since inflammation is central to the development of cancer cachexia, glycine supplementation represents a simple, safe and promising treatment. We tested the hypothesis that glycine supplementation reduces skeletal muscle inflammation and preserves muscle mass in tumor-bearing mice.

METHODS:

To induce cachexia, CD2F1 mice received a subcutaneous injection of PBS (control, n = 12) or C26 tumor cells (n = 32) in accordance with the protocols developed by Murphy et al. [Murphy KT, Chee A, Trieu J, Naim T, Lynch GS. Importance of functional and metabolic impairments in the characterization of the C-26 murine model of cancer cachexia. Dis Models Mech 2012;5(4):533-545.]. Subcutaneous injections of glycine (n = 16) or PBS (n = 16) were administered daily for 21 days and at the conclusion of treatment, selected muscles, tumor and adipose tissue were collected and prepared for Real-Time RT-PCR or western blot analysis.

RESULTS:

Glycine attenuated the loss of fat and muscle mass, blunted increases in markers of inflammation (F4/80, P = 0.01 & IL-6 mRNA, P = 0.01) and atrophic signaling (MuRF, P = 0.047; atrogin-1, P = 0.04; LC3B, P = 0.06 and; BNIP3, P = 0.10) and tended to attenuate the loss of body mass (P = 0.07), muscle function (P = 0.06), and oxidative stress (GSSG/GSH, P = 0.06 and DHE, P = 0.07) seen in tumor-bearing mice. Preliminary studies that compared the effect of glycine administration with isonitrogenous doses of alanine or citrulline showed that the observed protective effect was specific to glycine.

CONCLUSIONS:

Glycine protects skeletal muscle from cancer-induced wasting and loss of function, reduces the oxidative and inflammatory burden, and reduces the expression of genes associated with muscle protein breakdown in cancer cachexia. Importantly, these effects were glycine specific.

Front Neurol. 2012 Apr 18;3:61. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00061. eCollection 2012.

The effects of glycine on subjective daytime performance in partially sleep-restricted healthy volunteers.

Bannai M1, Kawai N, Ono K, Nakahara K, Murakami N.

Approximately 30% of the general population suffers from insomnia. Given that insomnia causes many problems, amelioration of the symptoms is crucial. Recently, we found that a non-essential amino acid, glycine subjectively and objectively improves sleep quality in humans who have difficulty sleeping. We evaluated the effects of glycine on daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and performances in sleep-restricted healthy subjects. Sleep was restricted to 25% less than the usual sleep time for three consecutive nights. Before bedtime, 3 g of glycine or placebo were ingested, sleepiness, and fatigue were evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) and a questionnaire, and performance were estimated by personal computer (PC) performance test program on the following day. In subjects given glycine, the VAS data showed a significant reduction in fatigue and a tendency toward reduced sleepiness. These observations were also found via the questionnaire, indicating that glycine improves daytime sleepiness and fatigue induced by acute sleep restriction. PC performance test revealed significant improvement in psychomotor vigilance test. We also measured plasma melatonin and the expression of circadian-modulated genes expression in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) to evaluate the effects of glycine on circadian rhythms. Glycine did not show significant effects on plasma melatonin concentrations during either the dark or light period. Moreover, the expression levels of clock genes such as Bmal1 and Per2 remained unchanged. However, we observed a glycine-induced increase in the neuropeptides arginine vasopressin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the light period. Although no alterations in the circadian clock itself were observed, our results indicate that glycine modulated SCN function. Thus, glycine modulates certain neuropeptides in the SCN and this phenomenon may indirectly contribute to improving the occasional sleepiness and fatigue induced by sleep restriction.

The FASEB Journal. 2011;25:528.2

Dietary glycine supplementation mimics lifespan extension by dietary methionine restriction in Fisher 344 rats

Joel Brind, Virginia Malloy, Ines Augie, Nicholas Caliendo, Joseph H Vogelman, Jay A. Zimmerman, and Norman Orentreich

Dietary methionine (Met) restriction (MR) extends lifespan in rodents by 30–40% and inhibits growth. Since glycine is the vehicle for hepatic clearance of excess Met via glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT), we hypothesized that dietary glycine supplementation (GS) might produce biochemical and endocrine changes similar to MR and also extend lifespan. Seven-week-old male Fisher 344 rats were fed diets containing 0.43% Met/2.3% glycine (control fed; CF) or 0.43% Met/4%, 8% or 12% glycine until natural death. In 8% or 12% GS rats, median lifespan increased from 88 weeks (w) to 113 w, and maximum lifespan increased from 91 w to 119 w v CF. Body growth reduction was less dramatic, and not even significant in the 8% GS group. Dose-dependent reductions in several serum markers were also observed. Long-term (50 w) 12% GS resulted in reductions in mean (±SD) fasting glucose (158 ± 13 v 179 ± 46 mg/dL), insulin (0.7 ± 0.4 v 0.8 ± 0.3 ng/mL), IGF-1 (1082 ± 128 v 1407 ± 142 ng/mL) and triglyceride (113 ± 31 v 221 ± 56 mg/dL) levels compared to CF. Adiponectin, which increases with MR, did not change in GS after 12 w on diet. We propose that more efficient Met clearance via GNMT with GS could be reducing chronic Met toxicity due to rogue methylations from chronic excess methylation capacity or oxidative stress from generation of toxic by-products such as formaldehyde. This project received no outside funding.

J Am Heart Assoc. 2015 Dec 31;5(1). pii: e002621. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002621.

Plasma Glycine and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Suspected Stable Angina Pectoris.

Ding Y, Svingen GF, Pedersen ER, Gregory JF, Ueland PM, Tell GS, Nygård OK.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Glycine is an amino acid involved in antioxidative reactions, purine synthesis, and collagen formation. Several studies demonstrate inverse associations of glycine with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Recently, glycine-dependent reactions have also been linked to lipid metabolism and cholesterol transport. However, little evidence is available on the association between glycine and coronary heart disease. Therefore, we assessed the association between plasma glycine and acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

METHODS AND RESULTS:

A total of 4109 participants undergoing coronary angiography for suspected stable angina pectoris were studied. Cox regression was used to estimate the association between plasma glycine and AMI, obtained via linkage to the CVDNOR project. During a median follow-up of 7.4 years, 616 patients (15.0%) experienced an AMI. Plasma glycine was higher in women than in men and was associated with a more favorable baseline lipid profile and lower prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (all P<0.001). After multivariate adjustment for traditional coronary heart disease risk factors, plasma glycine was inversely associated with risk of AMI (hazard ratio per SD: 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.98; P=0.017). The inverse association was generally stronger in those with apolipoprotein B, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or apolipoprotein A-1 above the median (all Pinteraction≤0.037).

CONCLUSIONS:

Plasma glycine was inversely associated with risk of AMI in patients with suspected stable angina pectoris. The associations were stronger in patients with apolipoprotein B, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or apolipoprotein A-1 levels above the median. These results motivate further studies to elucidate the relationship between glycine and lipid metabolism, in particular in relation to cholesterol transport and atherosclerosis.