The Observations of George Catlin

In 1860, after thirty years of travel as an artist and ethnographer, after observing over one hundred fifty tribes of Native Americans in both North and South America, after completing over five hundred paintings and publishing several books on his travels in the American frontier and in Europe, George Catlin wrote a short book of observations on the health practices of the American Indians. The forty-page volume became a best-seller and Catlin made sure it was kept in print until his death in 1872; yet the book is almost unknown today, even among the historians who oversee his collection, now housed in the Smithsonian Museum.

The book was called Shut Your Mouth (. . . and Save Your Life); its subject was the superb health of the Native Americans. While Catlin does not give precise details on native diets the way Dr. Price did, he does provide a fascinating corroboration of Price’s findings, one that we come close to explaining only today, after one hundred fifty years of intervening scientific discoveries. George Catlin’s message is timely, and may well provide a missing link for those who have followed Dr. Price’s principles and protocol for some time, but with less success than they had hoped.

ON A MISSION

George Catlin’s artistic career was inspired by a delegate of fifteen “noble and dignified” Indians visiting Philadelphia. The attorney-turned-painter then headed west to document the rapidly disappearing Native Americans, “on a mission of becoming their historian.”1 Making his base in St. Louis, he took five trips between 1830 and 1836, the first accompanied by General William Clark of Lewis and Clark fame. Catlin visited eighteen relatively isolated tribes on the upper Missouri River, including the Pawnee, Omaha, Ponca, Mandan, Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine and Blackfeet. Many later trips ranged from the Aleutian Islands to Patagonia.

In the years before photography—and during the time the U.S. government had openly instituted a policy of eradicating the Native Americans—Catlin was the first American artist to travel west of the Mississippi and paint portraits of the American Indians from life in their native habitat. His over five hundred paintings— from portraits to battle scenes—along with hundreds of artifacts and volumes of notes about native traditions amassed during his first six years of study, formed his “Indian Gallery,” which eventually came to rest in the Smithsonian Museum.

Welcomed by the American Indians—before other white men had given them reason to be distrustful—Catlin lived with them as their guest and ate their food. A naturally gifted linguist, he was able to gain access to their sacred rituals, hunting techniques and games. Driven by his own passion, as a “friend to the Indians” before they were “lost forever,” Catlin’s entire thirty years of travel in North and South America were entirely self financed.2

SUPERB HEALTH

As a pioneering anthropologist, Catlin recorded his observations of Native American physical characteristics in a manner remarkably similar to those of Dr. Price in his classic book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, one hundred years later.3 Like so many early observers, Catlin was struck by the beauty of their teeth. “These people, who talk little and sleep naturally, have no dentists nor dentifrice, nor do they require either; their teeth almost invariably rise from the gums and arrange themselves as regular as the keys of a piano; and without decay or aches, preserve their soundness and enamel, and powers of mastication.”4

Like Dr. Price, George Catlin looked at skulls, noting “the beautiful formation and polish of the teeth in these skulls.” Like Price, he was concerned about the effects of western diets on their health: “. . . the most beautiful of them, which had chewed Buffalo meat for 25 years or a half Century, are now chewing Bread. . . ”

Their traditional food was simple: “Food of this tribe, fish, venison, vegetables. . . This Tribe I found living entirely in their primitive state; their food, Buffalo flesh and Maize, or Indian corn.”

Catlin’s interest in skulls led him to conclude that the death among Native American children was very low. In searching through a graveyard, “I was forcibly struck with the almost incredibly small proportion of crania of children; and even more so, in the almost unexceptional completeness and soundness (and total absence of malformation) of their beautiful sets of teeth, of all ages.”

“Shar-re-tar-rushe, an aged and venerable Chief of the Pawnee-Picts, a powerful Tribe living on the headwaters of the Arkansas River, at the base of the Rocky Mountains, told me in answer to questions, ‘we very seldom lose a small child—none of our women have ever died in childbirth—they have no medical attendance on these occasions—we have no Idiots or Lunatics —nor any Deaf and Dumb, or Hunch-backs, and our children never die in teething.’” The food of this tribe was “buffalo flesh and venison.”

In contrast, Catlin observed, “in London and other large towns in England, and cities of the Continent, on an average, one half of the human Race die before they reach the age of five years, and one half of the remainder die before they reach the age of 25 yeas, thus leaving one in four to share the chances of lasting from the age of 25 to old age.” He noted statistics describing 20,000 idiots and 35,000 lunatics in England. “The contrast between the two societies, of Savage and of Civil, as regards to the perfection and duration of their teeth, is quite equal to their Bills or Mortality.”

Like Price, Catlin was struck by the beauty, strength and demeanor of the Native Americans. “The several tribes of Indians inhabiting the regions of the Upper Missouri. . . are undoubtedly the finest looking, best equipped, and most beautifully costumed of any on the Continent.” Writing of the Blackfoot and Crow, tribes who hunted buffalo on the rich glaciated soils of the American plains, “They are the happiest races of Indian I have met—picturesque and handsome, almost beyond description.”

“The very use of the word savage,” wrote Catlin, “as it is applied in its general sense, I am inclined to believe is an abuse of the word, and the people to whom it is applied.”

Like Price, who argued against genetics as a cause of human disabilities, Catlin did not think that the diseases of civilized man were due to inherent flaws in the human physical makeup. “This enormous disproportion might be attributed to some natural physical deficiency in the construction of Man, were it not that we find him in some phases of Savage life, enjoying almost equal exemption from disease and premature death, as the Brute creations [animals]; leading us to the irresistible conclusion that there is some lamentable fault yet overlooked in the sanitary economy of civilized life.”

“I offer myself as a living witness, that whilst in that condition [living among them], the Native Races of North and South America are a healthier people, and less subject to premature mortality (save from accidents of War and the Chase, and also from Small-pox and other pestilential diseases introduced amongst them) than any Civilized Race in existence.”

As did Weston A. Price one hundred years later, Catlin noted the fact that moral and physical degeneration came together with the advent of civilized society. In his late 1830s portrait of “Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going to and Returning from Washington” Catlin painted him corrupted with “gifts of the great white father” upon his return to his native homeland. Those gifts including two bottles of whiskey in his pockets.

SHUT YOUR MOUTH

Returning from his last voyage in 1860, Catlin wrote: “If I were to endeavor to bequeath to posterity the most important Motto which human language can convey, it should be in three words—Shut your mouth.”

Catlin did not completely understand the fact that nutrient-dense diets allow for the development of wide faces with broad nostrils and maximum airway capacity from nose to lungs. Such development allows the well-formed individual to breathe in sufficient oxygen through the nostrils, making mouth-breathing unnecessary. However, he did observe one interesting practice among nursing mothers in all Native American cultures he visited, in both North and South America: In Shut Your Mouth he wrote: “All Savage infants amongst the various Native Tribes of America, are reared in cribs (or cradles) with the back lashed to a straight board; and by the aid of a circular, concave cushion placed under the head, the head is bowed a little forward when they sleep, which prevents the mouth from falling open; thus establishing the early habit of breathing through the nostrils. . . I was soon made to understand, both by their women and their Medicine Men, that it was done to insure their good looks, and prolong their lives.”

In fact, Catlin believed that the habit of sleeping with the mouth closed actually contributed to the optimal development of the teeth: “An Indian child is not allowed to sleep with its mouth open, from the very first sleep of its existence; the consequence of which is, that while the teeth are forming and making their first appearance, they meet (and constantly feel) each other; and taking their relative, natural, positions, form that beautiful and pleasing regularity which has secured to the American Indians, as a race, perhaps the most manly and beautiful mouths in the world.”

Catlin notes: “The Savage Mother, instead of embracing her infant in her sleeping hours, in the heated exhalation of her body, places it at arm’s length from her, [in the cradleboard] and compels it to breathe the fresh air, the coldness of which generally prompts it to shut the mouth . . . The results of this habit are, that Indian adults invariably walk erect and straight, have healthy spines, and sleep upon their backs, with Robes wrapped around them, with the head supported by some rest, which inclines it forward. . . and their sleep is therefore always unattended with the nightmare or snoring.”

Catlin contrasted the universal Native American wisdom of creating a life-long nasal breathing habit both day and night in his illustration of the sleeping habits of “Civilized Man. . . their mouths wide open—the very pictures of distress— of suffering, of Idiocy, of Death. There is no animal in nature, excepting man, that sleeps with its mouth open. . . If man’s unconscious existence for nearly one-third of the hours of his breathing life depends, from one moment to another, upon the air that passes through his nostrils; and his repose during those hours, and his bodily health and enjoyment between them, depend upon the soothed and tempered character of the currents that are passed through his nose to his lungs, how mysteriously intricate in its construction and important in its functions is that feature, and how disastrous may be the omission in education which sanctions a departure from the full and natural use of this wise arrangement!”

THE BREATHING PRINCIPLE

One hundred fifty years ago, George Catlin made a critical observation regarding the hierarchy of physiological functions required for health. “Man can exist several days without food, but about as many minutes without the action of his lungs. . . Rest assured that the great secret to life is the breathing principle.”

According to Dr. Raymond Silkman, “Airway capacity is the biggest and most important part of the well-being of a human being. . . It is important to stress the fact that breathing through the mouth and breathing through the nose have extremely disparate effects on the body. We are not designed to breathe through our mouths. The body is able to live by breathing through the mouth, but it suffers greatly for doing it.”5

To summarize his excellent article, published in Wise Traditions Winter/Spring 2006, Dr Silkman compares an underdeveloped cranium to an “over-packed suitcase,” and discusses how the resultant problems can affect the entire body. Lack of oxygenation or nourishment to cranial tissues and organs and improper drainage of waste products through the lymphatic system, in turn cause nerve conduction issues, hormonal imbalances and negative effects on brain function and mental clarity. Salivary pH drops or becomes acidic in mouth breathing. A forward head posture can develop, which in turn causes spinal misalignments, fatigue and fibromyalgia. The maxilla (upper jaw bone) also becomes underdeveloped, affecting the eyesight and facial aesthetics and further narrowing the nasal passages, which do not drain or function properly.

Mouthbreathing can further depress the development of the maxilla—and this underdevelopment is the main cause of mouthbreathing in the first place. With underdevelopment of the maxilla—due to poor nutrition before conception andin utero—obstruction of the nasal passages sets the stage for sleep apnea, TMJ issues and migraine headaches. With mouth breathing, the lungs cannot oxygenate properly, thereby affecting the heart and even setting the stage for cancer. Cancer thrives in an anaerobic environment. Thus, having an underdeveloped facial structure negatively affects every cell in the body.

Many people struggling with their health may pass over the important clues in Dr. Silkman’s article because they do not think that they breathe through their mouths. But as Catlin points out: “Few people can be convinced that they snore in their sleep, for the snoring is stopped when they wake, and so with breathing through the mouth, which is generally the cause of snoring.” The obvious daytime mouth breathers are easy to spot, but the unconscious nighttime mouth-breathing habit can be present without detection, even with a spouse along side at night. And mouth breathing even at night can undermine our health. As Catlin puts it, ”. . . he renews his disease every night.”

Catlin’s book helped explain my own health problems, which persisted even though I was following a nutrient-dense diet, as I did not get the benefit of good airway development when starting life. Conversely, good facial structure from birth, which allows a person to breathe comfortably through his nose, can explain how a person remains healthy even while living a sedentary life, smoking, drinking and consuming junk foods. Blessed with optimum airway capacity, they function well even in the absence of good nutrition. Many older folks fit into this category, as before 1940 many westerners consumed a fairly good diet and enjoyed excellent facial development.

THE MYSTERIOUS REFINING PROCESS

Wrote Catlin: “The mouth of man. . . was made for the reception and mastication of food for the stomach, and other purposes, but the nostrils, with their delicate and fiborous linings for purifying and warming the air in its passage, have been mysteriously constructed, and designed to stand guard over the lungs. . . we are again more astonished when we see the mysterious sensitiveness of that organ instinctively and instantaneously separating the gases, as well as arresting and rejecting the material impurities of the atmosphere. . . The atmosphere is nowhere near pure enough for man’s breathing until it has passed this mysterious refining process.”

Today we know that nitric oxide is a critical component of that mysterious refining process. Dr. Silkman writes, “Breathing through the nose creates an avenue of air that’s moisturized, humidified and even somewhat filtered. Furthermore, when we breathe through our nose, the air passing through the nasal airway and contacting the turbinates—shelf-like bony structures—is slowed down. This allows the proper mixing of the air with an amazing gas produced in the nasal sinuses called nitric oxide (NO). Nitric oxide is secreted into the nasal passages and is inhaled through the nose. It is a potent vasodilator, and in the lungs it enhances the uptake of oxygen. Nitric oxide is also produced in the walls of blood vessels and is critical to all organs.”

NATURAL AND WHOLESOME AIR

Catlin describes how Native American infants were trained to have good breathing practices from an early age. “I, who have seen some thousands of Indian women giving the breast to their infants, never saw an Indian mother withdrawing the nipple from the mouth of a young infant, without carefully closing its lips with her fingers. . . It requires no more than common sense to perceive that Mankind, like all of the Brute creations, should close their mouths when they close their eyes in sleep, and breathe through their nostrils. . . But in civilized societies, how often do we see the tender mother (if she gives the breast at all) lull it to sleep at the breast, and steal the nipple from the open mouth, which she ventures not to close, for fear of waking it and if consigned to the nurse, the same thing is done with the bottle.

“The Savage infant. . . breathing the natural and wholesome air, generally from instinct, closes its mouth during sleep; and in all cases of exception the mother. . . enforces Nature’ Law . . . until the habit is fixed for life. . . When I have seen a poor Indian woman in the wilderness, lowering her infant from the breast, and pressing its lips together as it falls asleep, fix its cradle in the open air, and afterwards looked into the Indian multitude for the results of such a practice, I have said to myself, ‘glorious education! such a Mother deserves to be the nurse of Emperors.’

“But when we turn to civilized life, with all of its comforts, its luxuries, its science, and its medical Skill, our pity is enlisted for the tender germs of humanity, brought forth and caressed in smothered atmospheres which they can only breathe with their mouths wide open. . . They should first be made acquainted with the fact that their infants don’t require heated air, and that they had better sleep with their heads out of the window than under their mother’s arms.”

Do modern childrearing practices contribute to the scourge of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)? In the Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, October 2008, researchers reported that infants are less likely to succumb to SIDS with a fan on in the infant’s room.6 Furthermore, new studies show that swaddling, with the infant placed on the back, reduces SIDS.7 These studies prove the wisdom of the self-contained cradleboard, which protects the infant, as opposed to having the infant sleep with the mother and father, where it might be crushed in sleep or suffocated with loose bedding as it rolls over.

From Catlin’s observations of the universal use of cradle-boards among Native Americans, we can hypothesize that rearing infants in them would be less stressful for the infant, the mother and other family members. The large numbers of historical photographs showing Native Americans with contented and captivating infants in cradleboards also supports this theory.8

SLEEP APNEA

George Catlin’s comments on nightmares and the associated “night terrors” actually describes sleep apnea: “. . . no person on earth who has waked from a fit of the nightmare will dispute the fact that when consciousness came, he found his mouth and throat wide open, and parched with dryness. . . Every attack of the nightmare, I proclaim, is the beginning of death!. . .Though the spasm lasted but a minute. . . death would have been the consequence. . . how awful to be so near death, and so often!”

“It is very evident that the back of the head should never be allowed, in sleep, to fall to a level with the spine; but should be supported by a small pillow, to elevate it a little, without raising the shoulders or bending the back, which should always be kept straight. . . When you lay your head upon a pillow, advance it a little forward, so as to imagine yourself in a gallery of a theater looking into the pit.”

He continues: “Lying on the back is thought by many to be an unhealthy practice; and a long habit of sleeping in a different position from infancy to old age may even make it so; but the general custom of the Savage Races, of sleeping in this position from infancy to old age, affords very conclusive proof, that if commenced in early life it is the healthiest for a general posture that can be adopted.”

Studies show Catlin’s advice to be sound: elevating the head at night is recommended by most sleep apnea websites as a way to reduce sleep apnea.9 From my own experience, elevating the head also has the effect of reducing nasal congestion, which seems to occur when I am in the reclining position. If blood flow to the sinus cavity causes congestion and obstructs nasal breathing when one is lying flat, with only a small pillow under the head, then mouth breathing is the only other option. The “lip seal” that holds the tongue forward and suctioned up in the maxilla at the roof of the mouth and out of the way of the airway, and which naturally occurs with closed-mouth breathing, will be lost. However, when one opens the mouth to breathe, the lip seal is broken. This releases the tongue and allows it to fall back into the throat to obstruct the airway and cause sleep apnea. In order to have a healthy night’s sleep, it is critical to have clear and unobstructed nasal passages in order to breathe only through the nose. By the simple measure of elevating the head to an angle where nasal congestion does not occur and the mouth can be kept shut, snoring and sleep apnea in many cases can be prevented.

Catlin believed that mouthbreathing at night affected the whole facial structure: “The whole features of the face are changed, the under jaw, unhinged, fails and retires, the cheeks are hollowed, and the cheekbones and the upper jaw advance, and the brow and upper eyelids are unnaturally lifted; presenting at once the leading features and expression of idiocy. . . In all of these instances there is a derangement and deformity of the teeth, and disfigurement of the mouth and the whole face.”

Both Dr. Price and George Catlin wondered why tuberculosis claimed so many lives in modern man. In Catlin’s day, the disease was called “consumption.” Catlin lost his wife and one of his children to pneumonia, and in his book he ponders the cause of respiratory illness, linking it to mouth breathing: ”I am compelled to believe . . . that a great proportion of the diseases prematurely fatal to human life, as well as mental and physical deformities, and the destruction of the teeth, are caused by the abuse of the lungs, in the Mal-respiration of sleep.”

“Infected districts communicate disease, infection attracts to it putrescence, and no other infected district can be so near the lungs as an infected mouth.”

Sleep apnea is more than just a minor inconvenience. According to surveys, 30-60 percent of adults snore, depending on age.10 The statistics on sleep apnea in the US show eighteen to twenty million Americans—approximately one in fifteen people—have diagnosed sleep apnea. Undiagnosed sleep apnea afflicts perhaps another seventeen million people.11

Recent studies have shown that Sleep Disordered Breathing is associated with Type II diabetes12—now epidemic of diabetes in this country. Up to 50 percent of people afflicted with diabetes have sleep apnea!13 Still more studies link sleep apnea with diabetes, obesity and GERD.14 Furthermore, people who suffer from sleep apnea are up to four times more likely to have a stroke and three times more likely to have a heart attack.15 Drowsy driving leads to at least one hundred thousand car crashes and over fifteen hundred deaths each year, according to the National Highway Safety Administration.16

A PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE

For the Native Americans, emphasis on conservation of breath at night and during the day was more than practical wisdom—it was a philosophy of life. As Catlin observed, “The American Savage often smiles, but seldom laughs; and he meets most of the emotions of life, however sudden and exciting they may be, with his lips and his teeth closed. He is, nevertheless, garrulous and fond of anecdote. Civilized people, who, from their educations, are more excitable, regard most exciting, amusing, or alarming scenes with the mouth open; as in wonder, astonishment, pain, pleasure, listening, etc. . . [But] the Savage, without the change of a muscle in his face, listens to the rumbling of the Earthquake, or the thunder’s crash, with his hand over his mouth; and if by the extreme of other excitement he is forced to laugh or to cry, his mouth is invariably hidden in the same manner.”

Catlin notes: “The proverb, as old and unchangeable as their hills, amongst the North American Indians; My son, if you would be wise, open first your Eyes, your Ears next, and last of all, your Mouth, that your words may be words of wisdom, and give no advantage to thine adversary.”

In his 1902 book, The Soul of an Indian, an Interpretation, Dr Charles A. Eastman, of the Santee Dakota writes the following: “The man who preserves his selfhood ever calm and unshaken by the storms of existence— not a leaf, as it were, astir on the tree, not a ripple upon the surface of the shining pool—his, in the mind of the unlettered sage, is the ideal attitude and conduct of life. . . . ‘Silence is the cornerstone of character. Guard your tongue in youth,’ said the old chief, Wabashaw, ‘and in age you may mature a thought that will be of service to your people.’”17

Where the yogis of India practice pranayama, the control of the breath, during conscious waking hours, our own American Indian yogis appear to have used control of the breath in the unconscious state while sleeping— by rote habit fixed during infancy—and to have achieved a fortunate conservation of life force to enhance their lives.

George Catlin could have been writing about esoteric yogic breathing practices when he states, “The lungs should be put to rest as a fond mother lulls her infant to sleep.”

“We are told that the breath of life was breathed into man’s nostrils— then why should we not continue to live by breathing in the same manner?”

Scholar Fiona MacDonald explains the history of the breath,18 noting that the ancients commonly linked the breath to a life force. The Hebrew Bible refers to God breathing the breath of life into clay to make Adam a living soul (nephesh, roughly “breather”). For the Greek philosopher Anaximenes (about 550 BC), the breath or pneuma was the primeval life force that bound the universe together; inhaling it invigorated the body. Similarly, in Indian yogic philosophy,prana is the cosmic energy that fills and maintains the body, manifesting in living beings as the breath. The fourth step in Raja Yoga is pranayama, or breath control, practiced because the breath is believed to influence markedly a person’s thoughts and emotions. Similarly, modern medicine relates hyperventilation to a disturbed psychological state.19

VITAL CAPACITY

The forty-year Framingham study,20 provides a surprising validation of Catlin’s conclusion that “the great secret to life is the breathing principal.” Researchers in the famous Framingham heart study found that “force vital capacity,” the maximum volume of air that a person can exhale after a maximum inhalation, is the primary predictor for longterm heath and vitality.21 Framingham researchers William B. Kannel and Helen Hubert state: “This pulmonary function measurement appears to be an indicator of general health and vigor and literally a measure of living capacity.”22According to Dr. Kannel, “Long before a person becomes terminally ill, vital capacity can predict life span.”23

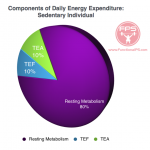

Some 80-90 percent of all of the body’s metabolic energy production is created by oxygen, with only 10-20 percent created from food and water. Furthermore, the respiratory system is responsible for eliminating 70 percent of the bodily metabolic waste. In 1924, Nobel Laureate Dr Otto Warburg linked lack of oxygen with cancer. “Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar.”24

HABITS AGAINST NATURE

“Life in all its fullness is Mother Nature obeyed,” wrote Dr. Price. Catlin formed a similar opinion: “Most habits against Nature, if not arrested, run into disease.”

“Air is an Elementary principal, created by the hand of God, who. . . creates nothing but perfections. . . sleep, which is the great renovator and regulator of health, and in fact the food of life, should be enjoyed in the manner which Nature has designed.”

Like Price, Catlin discusses the issue of heredity versus environment. “No diseases are natural,” he writes, “and deformities, mental and physical, are neither hereditary nor natural, but purely the result of accidents or habits.”

So wrote Dr. Price: “Neither heredity nor environment alone cause our juvenile delinquents and mental defectives. They are cripples, physically, mentally and morally, which could have and should have been prevented by adequate education and by adequate parental nutrition. Their protoplasm was not normally organized.”

Catlin believed that a change in childrearing practices could remedy the health problems of civilized man. “I have lived long enough, and observed enough, to become fully convinced of the unnecessary and premature mortality in civilized communities, resulting from the pernicious habit above described; and under the conviction that its most efficient remedy is in the cradle.” Of his book Shut Your Mouth, he said, “If I had a million dollars to give, to do the best charity I could with it, I would invest it in four millions of these little books, and bequeath them to the mothers of the poor, and the rich, of all countries. I would not get a monument or a statue, nor a medal; but I would make sure of that which would be much better—self credit for having bequeathed to posterity that which has a much greater value than money.”

We know from the work of Weston Price that attention to mouth closing from infancy is not enough to ensure proper facial development— diet is the key factor, starting from before conception. Nevertheless, Catlin’s observations provide the capstone to Price’s great edifice of nutritional research. By focusing on sleep positions that keep the mouth closed, and by insisting on cool, fresh air while sleeping, we can augment the benefits of a good diet.

We need to learn from the Native Americans and place more emphasis on optimizing “the breathing principle.” Breathing is something we do thirty thousand times a day, and breathing improperly, even for the one-third of our lives spent asleep, may undermine our vitality and even shorten our lifespan. Catlin observed that the American Indians practiced calm nasal breathing both day and night. Spiritual seekers for centuries have claimed that mastering the breath unlocks the mysteries of the universe. But, according to respiratory physiology expert Roger Price, learning to breathe properly is a fundamental, “mainstream” issue, not one to be avoided because it is a “sacred” issue or an “alternative care” issue.25

Thus, the Breathing Principle is a subject worthy of study, beginning with Catlin’s command, “Shut your mouth!”

SIDEBARS

The DANGERS OF Mouth Breathing

• The tongue no longer provides support for the upper jaw with resulting reduced upper arch size.

• The vault rises leading to reduction in the size of the nasal passages contributing to congestion of nose.

• The pH of saliva elevates leading to increased rate of caries.

• A tendency to upper respiratory tract infections often resulting in tonsillitis and enlarged adenoids.

• The medullary trigger resets at lower level leading to hyperventilation.

• The alkalinity of blood increases so less oxygen released from the blood. This is known as the Bohr Effect.

• Oxygen circulates the blood in the form of oxy-haemoglobin but reduced levels of carboxy-haemoglobin mean that less oxygen is released from the oxy-haemoglobin to enter the tissues so cells die.

• Smooth muscle spasm. Gastric reflux, asthma and bed wetting are commonly associated with chronic mouth-breathing. SOURCE: http://www.sleephotline.com/Sleep/categories/Breathing-Sleep.html

NATURAL VERSUS UNNATURAL SLEEP

Amusing drawing of “natural” and “unnatural” sleep from Catlin’s Shut Your Mouth. Says Catlin, “Unnatural sleep, which is irritating to the lungs and nervous system, fails to afford that rest which sleep is intended to give… They should first recollect that their natural food is fresh air…”

CRADLEBOARDS: A UNIVERSAL PRACTICE AMONG NATIVE AMERICANS

“Aissiniboine Mother and Child”

Photograph by Edward Curtis, 1928

“Nez Perce Babe”

Photograph by Edward Curtis, 1911

TREATING SLEEP APNEA

According to Dr. Steven Sue of Honolulu, when the mouth is closed and one breathes through the nose, a vacuum is formed which keeps the tongue up in the roof of the mouth, thereby preventing it from sliding back into the throat to obstruct the airway. “The lip seal is fundamental, almost invisible, and occurs naturally. It is found only in nose breathing! Zen masters since ancient times have known the secret. When the tongue is placed at the roof of the mouth, it prevents the tongue from falling into the back of the throat. The tongue is held forward and away from the back of the throat by the naturally occurring lip seal and a forward ‘tongue suction.’ Pacifiers and sippy cups keep the tongue low and away from the roof of the mouth. They encourage mouth breathing and tongue thrust; the same effects as thumb sucking and therefore, harmful to the developing child.”

Dr. Sue has invented several dental sleep apnea appliances designed with a tongue shelf for the tongue to rest on, which positions the tongue up against the maxilla. The key by which the tongue is held in the optimal upper position is the “lip seal” on his custom-made dental orthotic device, which prevents the vacuum from breaking. A closed mouth and normal nasal breathing creates this vacuum. An open mouth—as a result of structural imperfections, habit or blocked nasal passages—has no vacuum to hold the tongue forward, and therefore is free to fall back into the airway to cause an obstruction. SOURCE: nosebreathe.com

ADVICE FOR TODAY’S MOTHERS

Native American childrearing practices fly in the face of modern customs, and even may strike us as cruel to children. Childrearing experts today believe that infants should at all times be able to move their hands and legs freely, and while frowned on by government officials, sleeping with baby in close contact is highly encouraged in many circles.

The superb physical development of Native Americans is proof that confinement in a cradle board—usually until the second birthday—does not in any way hinder physical development. And while Indian mothers slept with their babies nearby, they did not snuggle them during the night.

According to health workers who have lived with tribes that still use cradle boards, the number one reason given for their use is safety—to keep the babies away from camp fires, and from wondering away while their mothers were working. (In European countries, babies were also swaddled to keep them safe; often the swaddled infants were hung on a hook near the hearth!) Modern mothers do not face the challenge of keeping babies away from fires, so do not need to restrain their infants in a cradle board. Nevertheless, swaddling cloths that keep baby’s arms and legs from moving are coming back into use, as they can have a very calming effect on the infant. And all mothers are now advised to put their infants on their backs to sleep, to reduce the risk of SIDS. Comfortable inflatable head rests are now available for babies, to help keep them on their backs with heads tilted slightly forward. Put to bed in this manner, wrapped in a warm swaddling cloth and with a window open to allow fresh air into the room, babies can receive all the benefits of the cradle board in a modern setting.

And now to answer the question you have all been wanting to ask: Native American mothers didn’t use diapers, of course. Instead, they wrapped the baby in soft, absorbant spagnam moss, replacing it about once every twenty-four hours.

Sally Fallon Morell

HOW TO DETERMINE YOUR VITAL CAPACITY

Vital Capacity is a measure of the amount of air that the lungs can hold; in a clinical setting this is determined using lung volume bags. But it is possible to measure your vital capacity using a balloon, a piece of string and a ruler. The procedure is to blow into a balloon several times to loosen it, then to blow in with one long exhalation, then tie the balloon off and measure the circumference at the widest point. The vital capacity is then determined by comparing the diameter of the balloon to fixed numbers on a graph.

For further information, visit wiki.answers.com/Q/How_do_you_measure_vital_capacity_at_the_bedside orwww.teachingk-8.com/archives/integrating_science_in_your_classroom/measuring_lung_capacity_by_john_cowens.html.

REFERENCES

1. Catlin, George, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Conditions of the North American Indians, Volume 1, p 2.

2. Ibid, 15-31.

3. Price, Weston A. DDS, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, Price Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, 1939.

4. This and all quotes following by George Catlin are from: Catlin, George, Shut Your Mouth… and Save Your Life 4th Edition, 1870, N. Truebner and Co, (now available at: Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, Montana); also available in digital form at http://www.members.westnet.com.au/pkolb/indians.pdf.

5. Silkman, Raymond, DDS. Is it Mental or is it Dental?—Cranial & Dental Impacts on Total Health. Wise Traditions, quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Spring 2005- Winter 06.

6. Coleman-Phox, Kimberly, MD, and others. Use of a Fan During Sleep and the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):963- 968.

7. Gerard, Claudia M. MD. Spontaneous Arousals in Supine Infants While Swaddled and Unswaddled During Rapid Eye Movement and Quiet Sleep. PEDIATRICS Vol. 110 # 6 December 2002, p e70; Franco, Patricia MD, PhD. Influence of Swaddling on Sleep and Arousal Characteristics of Healthy Infants. PEDIATRICS Vol. 115 # 5 May 2005, pp 1307-1311.

8. http://www.care2.com/c2c/photos/view/255/224457095/Cradleboards/.

9. www.sleepassociation.org, http://www.sleepapnea.org/resources/pubs/treatment. html; Skinner, Margot. Elevated Posture for the Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep and Breathing. Springer Berlin Volume 8, Number 4. October, 2004

10. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snoring

11. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sleep_apnea;

12. Reichmuth, Kevin J. Association of Sleep Apnea and Type II Diabetes. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol 172, pp1590-1595, (2005).

13. www.sleepandyou.com/sleep-connections-diabetes.htm.

14. Ayazi, Shahin. Obesity and Gastroesophageal Reflux: Quantifying the Association Between Body Mass Index, Esophageal Acid Exposure and Lower Esophageal Sphincter Status in a Large Series of Patients with Reflux Symptoms.J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 August; 13(8): 1440–1447.

15. National Sleep Foundation, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/sleepapnea.html

16. www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/human/drows_driving/ – 10k – 2006-03-09.

17. Eastman, Charles A, Dr. Ohiyesa, The Soul of an Indian, an Interpretation. London, 1902, 1911.

18. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breath.

19. http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Hyperventilation.

20. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Framingham_Heart_Study; http://www.nih.gov/ Also see another 30 year study with the same conclusion: http://www.buffalo.edu/news/4857 (lung function and death risk relationship) Holger Schunemann, MD “It is surprising that this simple measurement has not gained more importance as a general health assessment tool.”

21. Vital Capacity” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vital_capacity.

22. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ http://www.nih.gov/.

23. http://breathing.com/articles/clinical-studies.htm; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/.

24. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_Heinrich_Warburg.

25. www.buteykoabc.com; www.breathingwell.org; www.levityhealth.com.au.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Fall 2009. |