In this excerpt from The Happiness Diet, discover how Procter & Gamble convinced people to forgo butter and lard for cheap, factory-made oils loaded with trans fat.

Before highways and before railroads, America conducted her commerce via steamship over water through a system of rivers, canals, and lakes. In the 1800s, Cincinnati was the heart of the developed United States. At the time it was known to the world as Porkopolis. That’s because not so long ago, the most widely consumed meat in this nation was swine.

Before highways and before railroads, America conducted her commerce via steamship over water through a system of rivers, canals, and lakes. In the 1800s, Cincinnati was the heart of the developed United States. At the time it was known to the world as Porkopolis. That’s because not so long ago, the most widely consumed meat in this nation was swine.

This was before refrigeration. The biggest enemy of 19th-century butchers was spoilage. Eating cows didn’t make a whole lot of sense: Distributing the meat of a freshly killed 1,500-pound animal before it went bad was difficult without roads and temperature-controlled trains. But pigs are fatty, which makes them excellent for salt curing because they don’t lose flavor.

Cincinnati is on the Ohio River, which flows to the Mississippi River, which leads to the ever-important port of New Orleans. From the mouth of the mighty Mississippi, Porkopolis distributed meat throughout the coastal southern United States. The by-products of pork production meant that the burgeoning metropolis was also home to many tanneries, boot makers, and upholsters. Animal fats were hot commodities, as they were rendered and molded into soap and candles. Breaking down pigs was a highly efficient process known as the disassembly line — an idea that would later be reverse-engineered by Henry Ford to produce automobiles.

A major economic depression in the 1870s caused two important citizens of Porkopolis to join forces in order to cut costs and survive the bear market. They formed a company that would eventually be responsible for the greatest dietary shift in our country’s history. William Procter brought his candle-making business to the states after a fire destroyed his business in England. James Gamble fled Ireland during the Great Potato Famine and became a soap manufacturer. In a twist of fate, the two men happened to marry sisters in Cincinnati. Together, the brothers-in-law formed Procter & Gamble, a soap- and candle-manufacturing operation.

“What was garbage in 1860 was fertilizer in 1870, cattle feed in 1880, and table food and many things else in 1890.” — Popular Science, on cottonseed

At the time, soap was sold in huge wheels that were sliced into custom-sized portions at general stores. Procter and Gamble decided to take a chance by mass-producing individually wrapped bars of soap. To pull this off, the brother-in-laws needed to drastically reduce the price of their raw ingredients, which meant finding a replacement for expensive animal fats. They settled on a mix of palm and coconut oils and created the first soap that floated in water — a handy invention when clothes and dishes alike were washed in a sudsy basin. Hard pressed to come up with a name for this new product, Procter looked to the bible for inspiration and found it in Psalm 45:8: “All thy garments smell of myrrh, and aloes, and cassia, out of the ivory palaces, whereby they have made thee glad.” The word Ivory was trademarked, and in short order Americans all over the country would know the purity of this soap.

Oddly enough, the company to thank for the fact that America now eats so much vegetable oil has never produced much in the way of food. Thanks to Procter & Gamble the United States boosted the production of a waste product of cotton farming, cottonseed oil. To ensure a steady, cheap supply for soap production the company formed a subsidiary in 1902 called Buckeye Cotton Oil Co. Before processing, cottonseed oil is cloudy red and bitter to the taste because of a natural phytochemical called gossypol (it’s used today in China as male birth control) and is toxic to most animals, causing dangerous spikes in the body’s potassium levels, organ damage, and paralysis.

An issue of Popular Science from the era sums up the evolution of cottonseed nicely: “What was garbage in 1860 was fertilizer in 1870, cattle feed in 1880, and table food and many things else in 1890.” But it entered our food supply slowly. It wasn’t until a new food-processing invention of hydrogenation that cottonseed oil found its way into the kitchens of America’s restaurants and homes.

Edwin Kayser, a German chemist, wrote to Procter & Gamble on October 18, 1907, about a new chemical process that could create a solid fat from a liquid. The company’s researchers had been interested in producing a solid form of cottonseed oil for years, and Kayser described his new process as “of the greatest possible importance to soap manufacturers.” The company purchased US rights to the patents and created a lab on the Procter & Gamble campus, known as Ivorydale, to experiment with the new technology. Soon the company’s scientists produced a new creamy, pearly white substance out of cottonseed oil. It looked a lot like the most popular cooking fat of the day: lard. Before long, Procter & Gamble sold this new substance (known today as hydrogenated vegetable oil) to home cooks as a replacement for animal fats.

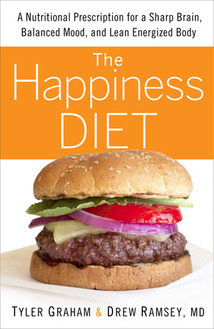

Procter & Gamble filed a patent application for the new creation in 1910, describing it as “a food product consisting of a vegetable oil, preferably cottonseed oil, partially hydrogenated, and hardened to a homogeneous white or yellowish semi-solid closely resembling lard. The special object of the invention is to provide a new food product for a shortening in cooking.” They came up with the name Crisco, which they thought conjured up crispness, freshness, and cleanliness.

Convincing homemakers to swap butter and lard for a new fat created in a factory would be quite a task, so the new form of food needed a new marketing strategy. Never before had Procter & Gamble — or any company for that matter — put so much marketing support or advertising dollars behind a product. They hired the J. Walter Thompson Agency, America’s first fullservice advertising agency staffed by real artists and professional writers. Samples of Crisco were mailed to grocers, restaurants, nutritionists, and home economists. Eight alternative marketing strategies were tested in different cities and their impacts calculated and compared. Doughnuts were fried in Crisco and handed out in the streets. Women who purchased the new industrial fat got a free cookbook of Crisco recipes. It opened with the line, “The culinary world is revising its entire cookbook on account of the advent of Crisco, a new and altogether different cooking fat.” Recipes for asparagus soup, baked salmon with Colbert sauce, stuffed beets, curried cauliflower, and tomato sandwiches all called for three to four tablespoons of Crisco.

Health claims on food packaging were then unregulated, and the copywriters claimed that cottonseed oil was healthier than animal fats for digestion. Advertisements in the Ladies’ Home Journal encouraged homemakers to try the new fat and “realize why its discovery will affect every family in America.” The unprecedented product rollout resulted in the sales of 2.6 million pounds of Crisco in 1912 and 60 million pounds just four years later. This new food bolstered the bottom line of a company whose other products were Ivory Soap, Lenox Soap, White Naphtha Laundry Soap, and Star Soap. It also helped usher in the age of margarine as well as low-fat foods.

Procter & Gamble’s claims about Crisco touching the lives of every American proved eerily prescient. The substance (like many of its imitators) was 50 percent trans fat, and it wasn’t until the 1990s that its health risks were understood. It is estimated that for every two percent increase in consumption of trans fat (still found in many processed and fast foods) the risk of heart disease increases by 23 percent. As surprising as it might be to hear, the fact that animal fats pose this same risk is not supported by science.

Reprinted from The Happiness Diet (c) 2011 by Drew Ramsey, MD and Tyler Graham. Permission granted by Rodale, Inc. Available wherever books are sold.

Good one. Sent it to some friends.